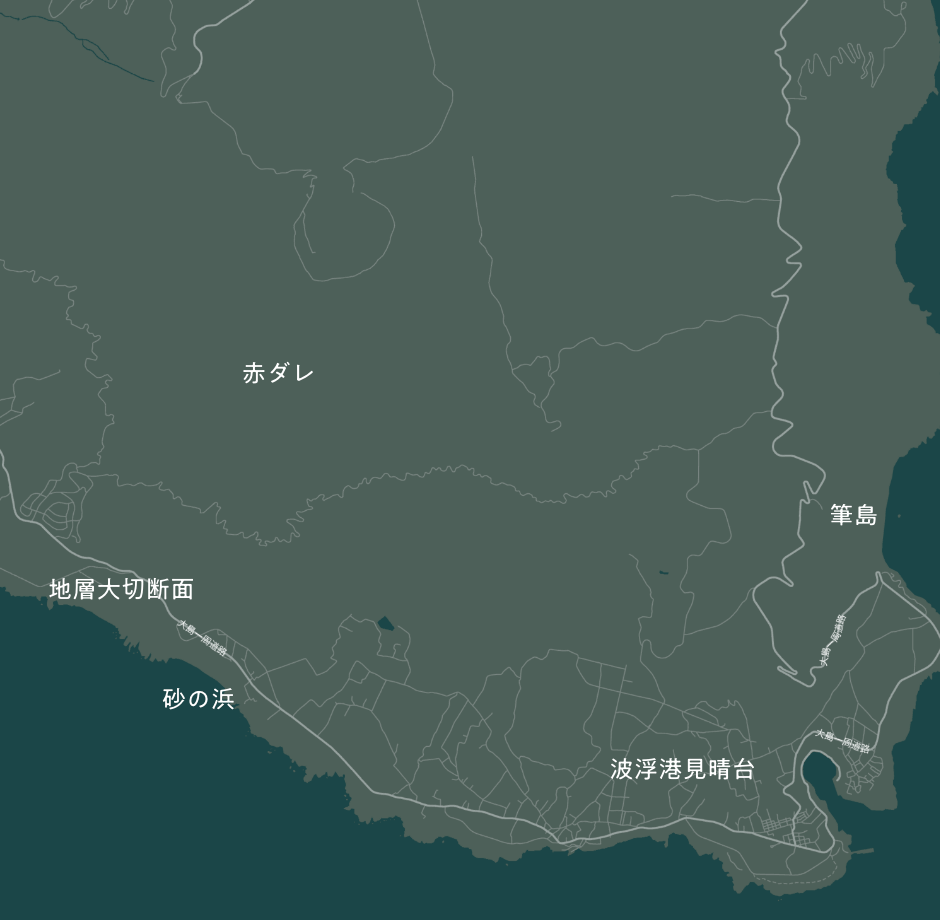

Upon arriving on Oshima, our first destination was "The Great Road Cut", where traces of over 100 major eruptions are exposed on a massive scale, stretching approximately 630 meters in length and rising 24 meters high.

"This bottommost layer dates back 20,000 years, meaning this place holds approximately 20,000 years of Earth's history,"

explained Mr. Kasuya, our guide. He's not only a geo-guide but also runs a diving shop on the island, making him a unique individual with extensive knowledge of both Oshima's land and sea.

Oshima experiences major eruptions roughly once every 200 years, and there's a theory that medium-sized eruptions occur about every 40 years.

"There are also preserved plant samples here, providing insights into climate changes and other factors,"

added Mr. Nakajima, intently observing the geological layers.

The volcanic activity on Oshima, regarded as one of Japan's most well-studied volcanoes, owes much of its understanding to the data collected from this geological site.

"These layers were formed from volcanic deposits, and such extensive exposure is rare worldwide. Researchers from around the globe visit this place. Some tourists merely take pictures though, comparing it to baumkuchen layers."

"That's a shame... In my case, studying the Himalayas requires imagination and piecing together partial hints. Here, you get to observe it more holistically. I envy you a lot,"

said Mr. Nakajima. Despite his usual quiet demeanor, when discussing geology and climbing, he becomes quite talkative.

Spread out before us is a pitch-black sandy beach, known as the "Black Sand Beach," a testament to the island's volcanic activity. During major eruptions, copious amounts of volcanic sand cascade down the streams and find their way to the ocean, creating this strikingly dark shoreline.

The sand travels down from the mountains above - it is a simple fact, yet Oshima's charm lies in how easily we can visualize such phenomena. This area also serves as a nesting ground for sea turtles, attracting a multitude of them during the nesting season.

We glance over at Mr. Nakajima, who was carefully picking up sand and observing it.

We stroll along the beach, only accessible during low tide, making our way towards "Fudeshima."

As the name suggests, Fudeshima (Brush Island) has a shape resembling a brush, but it is actually a solidified volcanic rock that filled a former lava channel. The surrounding area has been eroded by waves, and only the core remains. Originally, it was part of a volcano towering over 1,000 meters in height, with a history older than Oshima itself. "In 5,000 years, this landscape might be gone," Mr. Kasuya remarked.

Mr. Nakajima seemed to be as fascinated by the dikes running throughout the area as he is by Fudeshima itself.

"I've never seen a place with so many exposed dikes before," he said.

"It's no surprise that you'd use the term 'exposed dikes.' If you're a geologist, I'm sure you'd love this place," answered Mr. Kasuya.

Dikes are the traces left behind by magma cracking and flowing through the rocks. Here, gray ribbon-like dikes run throughout the landscape.

Armed with some knowledge, what might have appeared as mere streaks transforms into a landmark that allows us to connect more deeply with the Earth.

Mr. Nakajima continued to run his fingers along the dikes, feeling their texture.

The next day, we drove about 30 minutes southeast from Motomachi Harbor. From the hilltop, we could see a small port called Habu Port.

Surprisingly, volcanoes also played a significant role in shaping this place.

It used to be a plain plateau, but volcanic eruptions created a crater lake here. Later, it connected to the sea due to tsunamis caused by a major earthquake, and they developed it into a natural harbor, forming Habu Port. With good fishing grounds nearby, it thrived as a waiting port for favorable winds, boasting a history of prosperity. In the old photos shown to us by Mr. Kasuya, we saw the former bustling Habu Port filled with boats. Despite facing disasters like volcanic eruptions, people not only persevered but also made use of them. It's a place that embodies human resilience.

We headed to another eruption site that Mr. Kasuya recommended.

After passing through a lava field from the top of Mount Mihara and walking along a flat path for about an hour, it suddenly appeared before us - a deeply scarred and vividly red terrain.

This place, known as "Akadare" (Red Scars), is believed to have formed from an eruption that took place near the original swamp long before Mount Mihara even existed. Subsequent erosion along the swamp resulted in the dynamic landscape we see today. The name "red" comes from the lava, which remained at a high temperature and oxidized significantly upon contact with air. In short, it is the red of rust.

The contrast between the red and green here is breathtaking, and you can faintly see the lava flow in streaks, similar to the ones we witnessed yesterday that extended all the way to the sandy beach.