Dialogue Between Nature and Humanity

Toward the Future in the Harsh Northern Environment

Dialogue Between Nature and Humanity

Toward the Future in the Harsh Northern Environment

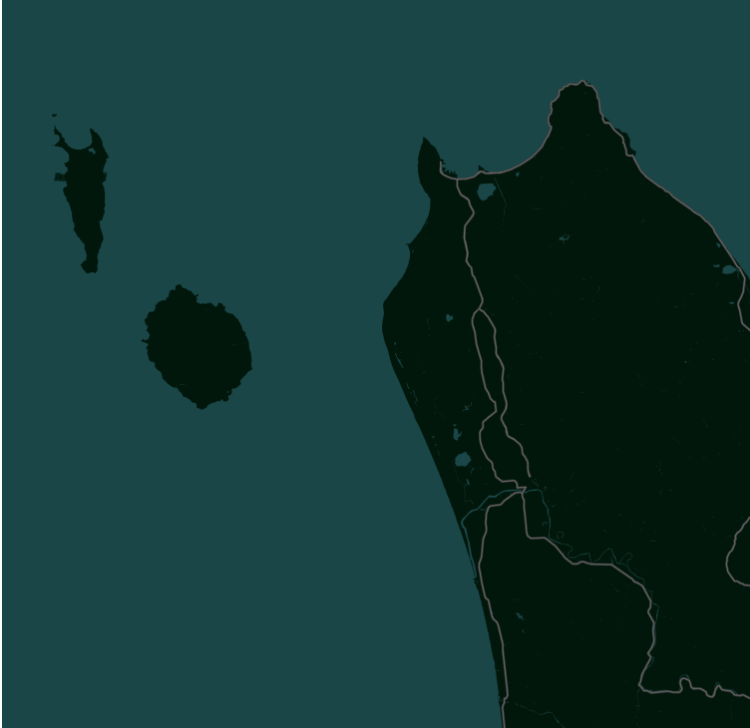

Rishiri-Rebun-Sarobetsu National Park: a place of dynamic and diverse landscapes, including mountains like Mount Rishiri, various alpine plants, and one of Japan's largest plain, the Sarobetsu Plain. As 2024 approaches, the park will celebrate its 50th anniversary.

While it stands as a major tourist destination, welcoming a multitude of visitors, the park also confronts a range of challenges.

In response, the dedicated guardians of the north work tirelessly, striving to discover solutions.

Within the northernmost national park, a dialogue unfolds between nature and people, carrying within it hints for a future of coexistence.

- Guides

- Shinya Okada / Hiroto Kumagai

- Location

- Rishiri-Rebun-Sarobetsu National Park

Photographer Hinano Kimoto

Writer Takumi Sakurais

People

Representative of Trail Works

Shinya Okada

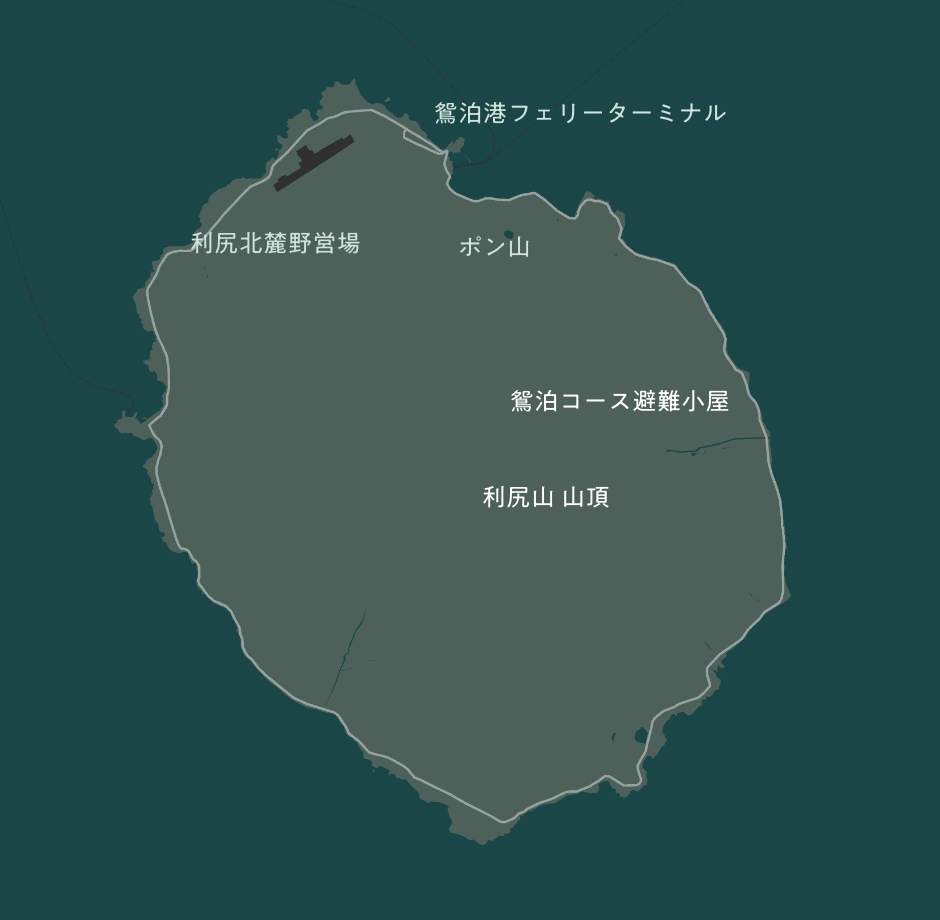

When he arrived on Rishiri Island as an active ranger, he witnessed the deteriorated state of the hiking trails, and in 2006, he established "Trailworks," a trail maintenance company on Rishiri Island. Under the guidance of Tetsuzo Okazaki from the "Daisetsuzan Yamaoritai (mountain guardians of Mount Daisetsuzan)," he learned about the "Kin-Shizen-Koho" construction method. Drawing inspiration from trail maintenance techniques abroad, he is dedicated to finding the most suitable methods for maintaining hiking trails on Mount Rishiri.

"A Fragile and Crumbling Mountain"

Hiking Trail Maintenance Project of Mount Rishiri

https://yamap.com/support-projects/925

#YAMAP #Crowdfunding

Nature Guide

Hiroto Kumagai

Born and raised on Rishiri Island, he initially began volunteering as a guide to the island's natural wonders. Four years ago, he became a certified nature park guide. He has climbed the local low mountain, Pon Mountain, which he maintains himself, over 1000 times in total.

Rebun Town Alpine Plant Culture Center

Seiji Murayama

Head of the Natural Environment Division at the Rebun Town Office. Responsible for conservation management of Rebun-atsumori-so and surveys of fallen trees. As a researcher, he also cultivates Rebun-atsumori-so using symbiotic fungi.

Chairman of Sarobetsu Agricultural Liaison Council

Hisaaki Yamamoto

Engaged in dairy farming in Toyotomi-cho, he actively participates in wetland conservation efforts. He also plays a significant role in the "Upper Sarobetsu Nature Restoration Council." In 2017, his initiative "Coexistence of Agricultural Land and Wetland for Sarobetsu Wetland Restoration" was recognized, and he received the "Ueno Award" from the The Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage, and Rural Engineering.

Sarobetsu Eco Network

Makoto Hasebe

At the Sarobetsu Eco Network based at the Ministry of the Environment's information facility, the "Sarobetsu Wetland Center," he serves as the secretary-general and is responsible for biodiversity conservation. In addition to wetland protection and management, he is also involved in bird surveys. The network regularly holds backyard tours for wetland conservation.

Town of Toyotomi Town Hall

Kazuki Kurokawa (right)

Masahiro Yamagata (left)

Employees of Toyotomi Town Hall, where Sarobetsu Wetland is located. Kazuki Kurokawa works in the Commerce and Tourism Section, undertaking various initiatives to promote awareness of the Sarobetsu Wetland. Masahiro Yamagata, although not related to his official duties, operates the "Eco Mo Project" in his personal capacity.