Drift Ice - Crafting the Circle of Life

Drift Ice - Crafting the Circle of Life

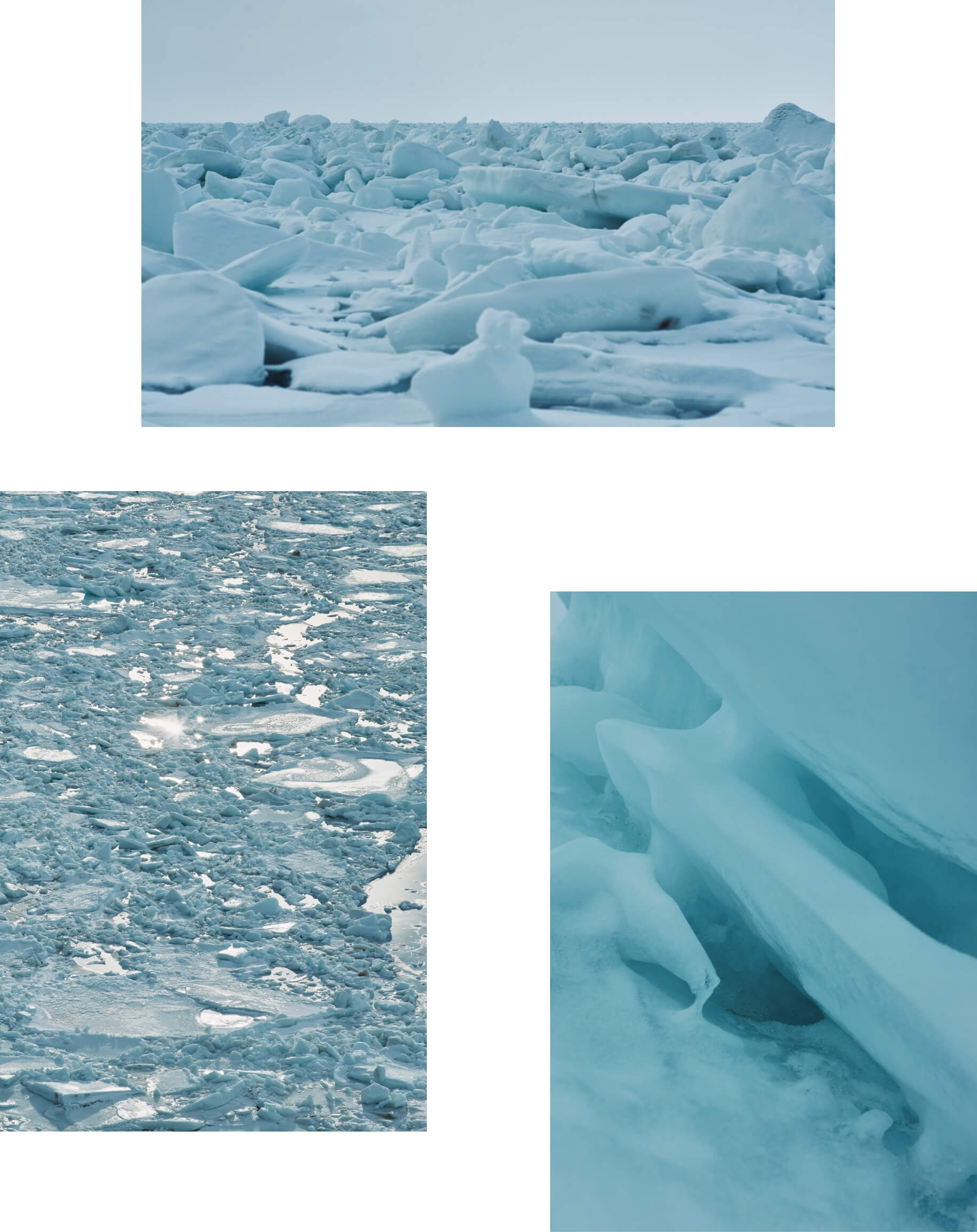

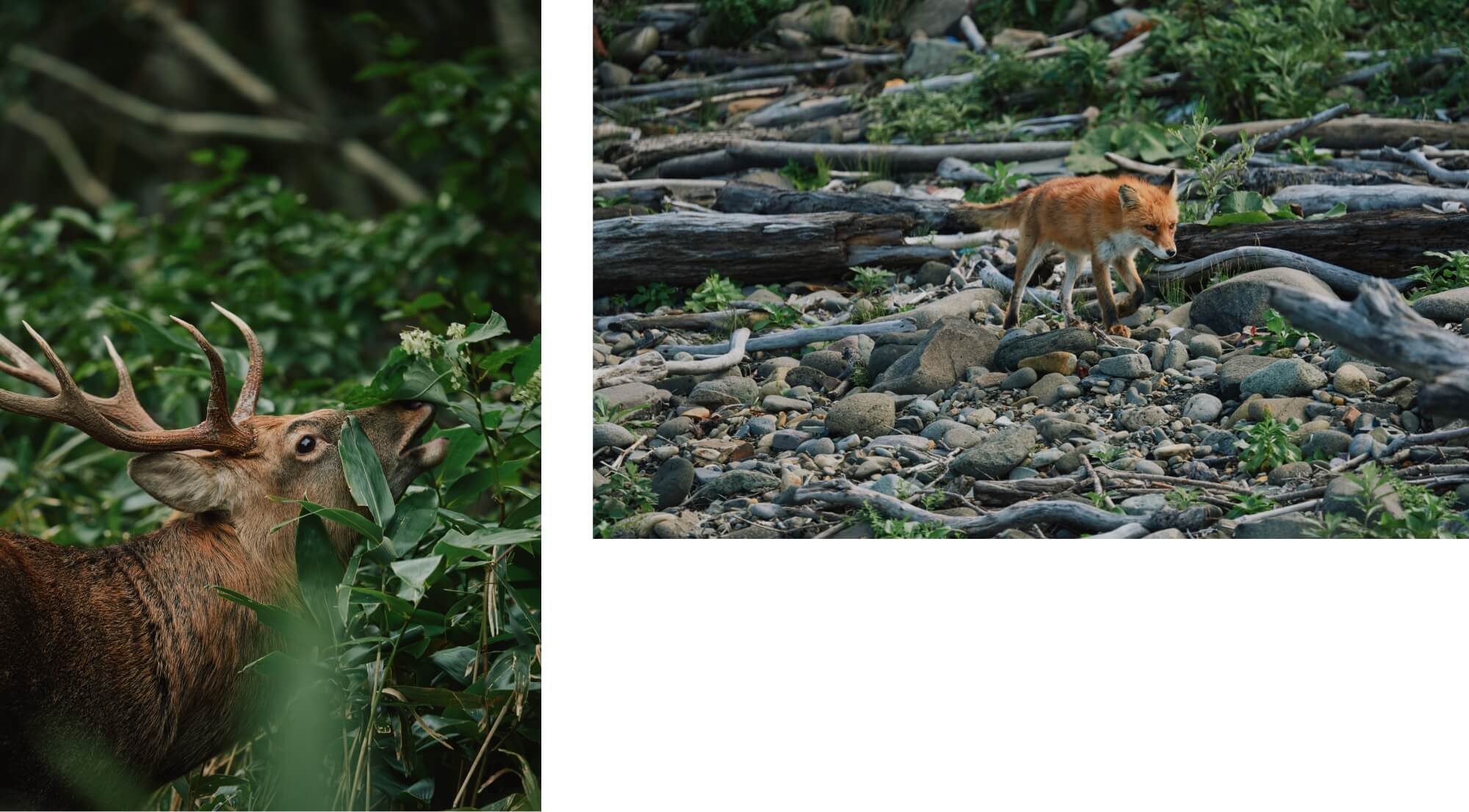

While Shiretoko boasts several number one distinctions in Japan, including the highest population of brown bears and the highest volume of salmon catch, all of these accolades originate from nature. The grand and rich nature of Shiretoko is said to be supported by drift ice. Eager to experience the circle of life beginning with drift ice, we embarked on a journey to Shiretoko National Park, commemorating its 60th anniversary this year.

- Guide

- Daisuke Imura (Ministry of the Environment)

- Location

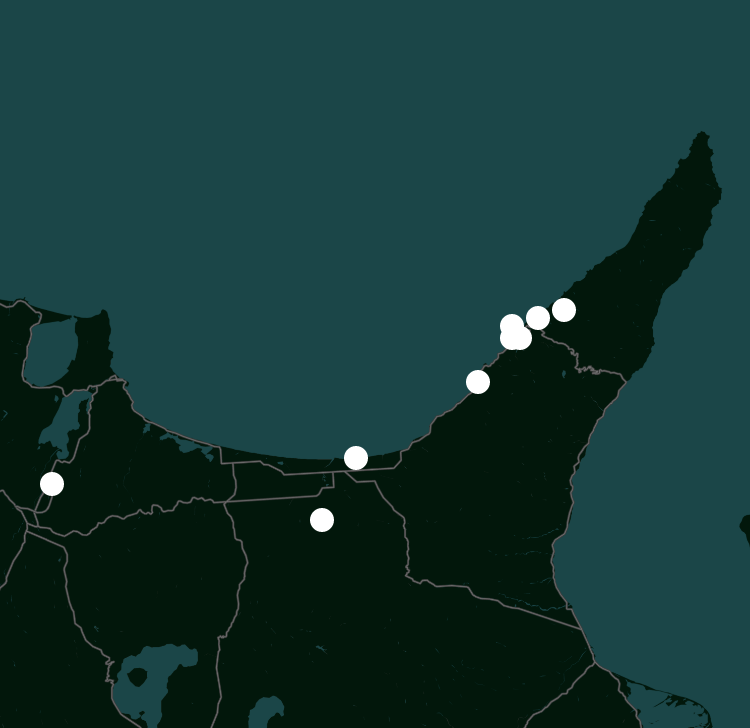

- Shiretoko National Park

Photographer Hinano Kimoto

Writer Takumi Sakurai

People

Public Interest Incorporated Foundation for Shiretoko Institute of Wildlife Management

Hajime Nakagawa

Former curator of the Shiretoko Museum. With over 40 years of experience, he has been observing Shiretoko's nature. Specializing in the ecology and conservation management of birds such as birds of prey, he continues to contribute to biodiversity conservation through publications and outreach activities. The foundation's annual "Shiretoko Nature Campus" attracts students from all over Japan.

Utoro Fisheries Cooperative

Akihiko Kosaka

Representative of Kyowa Gyogyobu Inc., which has been engaged in fixed net fishing in Utoro for many years. Known for his extensive knowledge of Shiretoko's sea, he has also contributed to maritime rescue efforts. In 2022, he opened the fish restaurant "OYAJI" in Utoro.

Shari Town Hall, Fisheries and Forestry Division

Takashi Mori

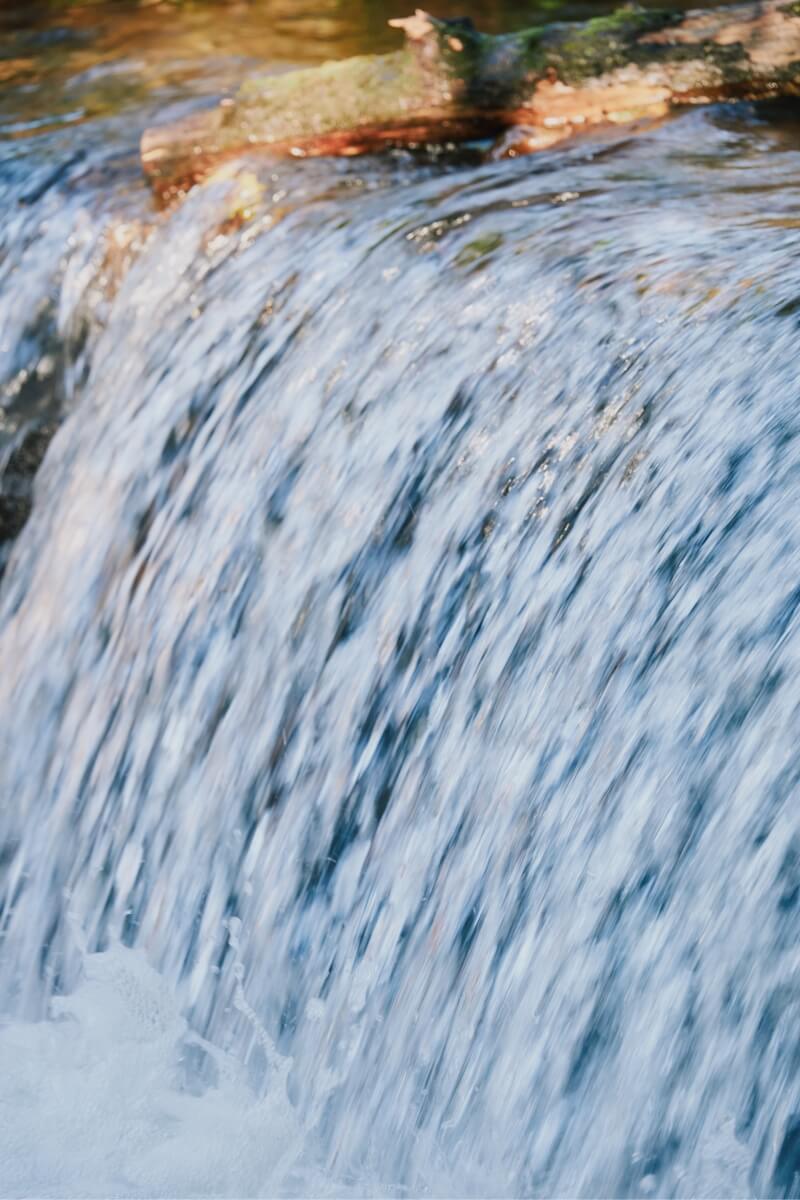

As an employee of the town hall, he is dedicated to the conservation and restoration of salmon and trout resources. He often participates in lectures and also appears in events for children under the alias "Salmon Takashi."

Freelance Guide

Hajime Terayama

After working for a travel agency specializing in remote areas such as Nepal, Tibet, and Mongolia, he joined the Shiretoko Foundation in January 2006. He served as the secretary-general of the Shiretoko Shari Association from 2019 and began working as a freelance guide in 2024. He also contributes to the development of the Hokkaido Higashi Trail.

Shiretoko Guide Shop "pikki"

Satoshi Wakatsuki

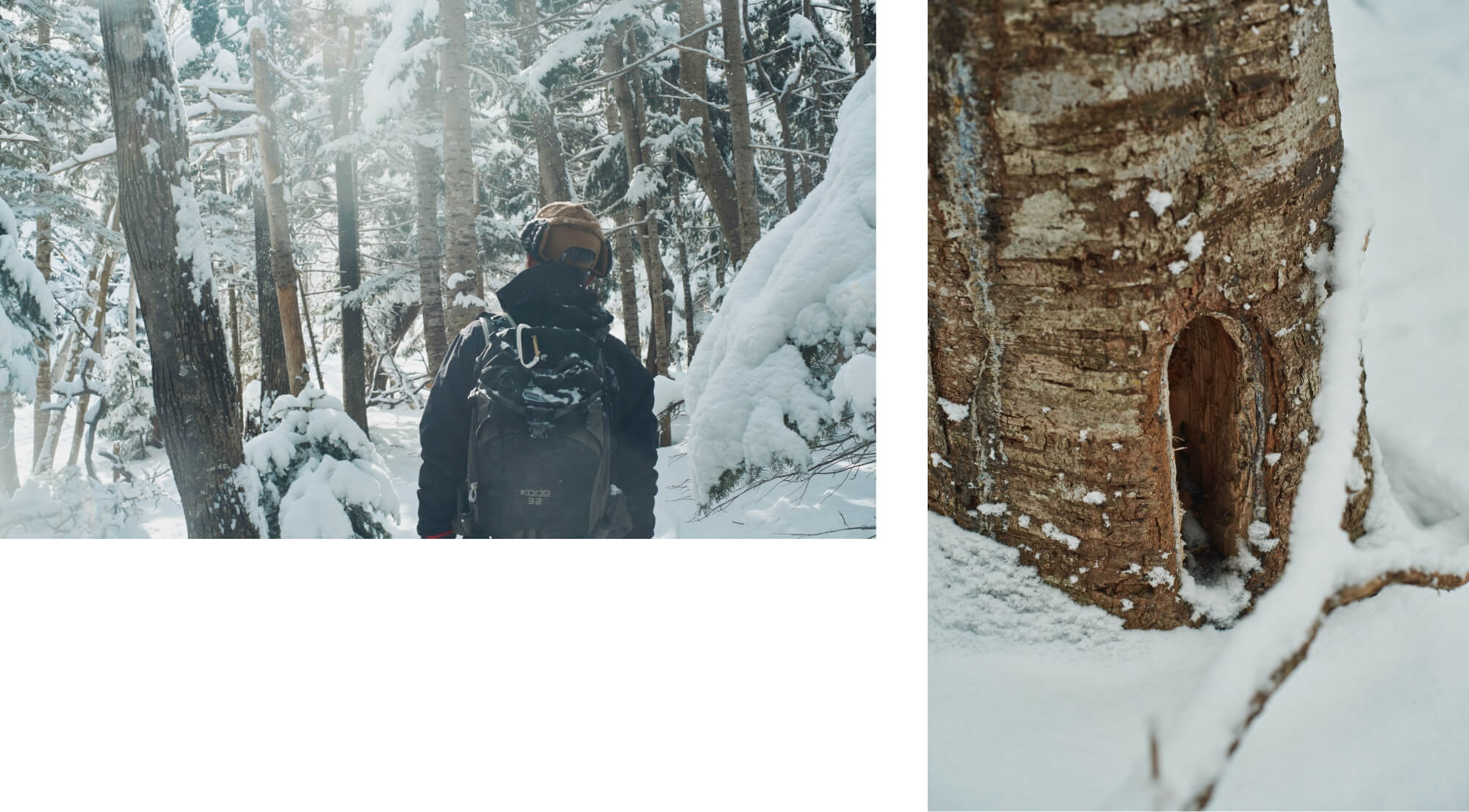

He has been working as a guide in Shiretoko for over 20 years. He mainly offers private guided tours and tailor-made tours. From spring to autumn, he conducts tours such as Shiretoko Goko Lakes Trekking, and in winter, he organizes snowshoe tours in Shiretoko Forest. He is a certified outdoor guide by the Governor of Hokkaido.

Ministry of Environment, Nature conservation office Utoro

Daisuke Imura

As a national park planning officer, he works on various initiatives to promote Japan's national parks as global destinations. This year, various events are planned to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the designation of Shiretoko National Park. In collaboration with The North Face, talk events and tours featuring Naoki Ishikawa and Yoki Tanaka are scheduled for September.

Drift Ice Free Diver

Yui Takagi

Born and raised in Shiretoko Utoro. She entered the world of scuba diving when she entered junior high school. In 2011, she was selected as one of the Japanese national team players for the AIDA Freediving World Championships. Since 2013, she has been organizing the drift ice diving event "ICE CUP." CUP」を主催している。

Artist

Airda

From Nerima Ward, Tokyo. The artist name, pronounced as "e-a-da," has been used since his band days in Tokyo. He enjoys both nature in Shiretoko and urban life in Shari Town. He holds music events with friends and also provides music for fashion shows.